The Counterfeiting of Robert Gray

by Nadine Akkerman & Pete Langman

September 2025

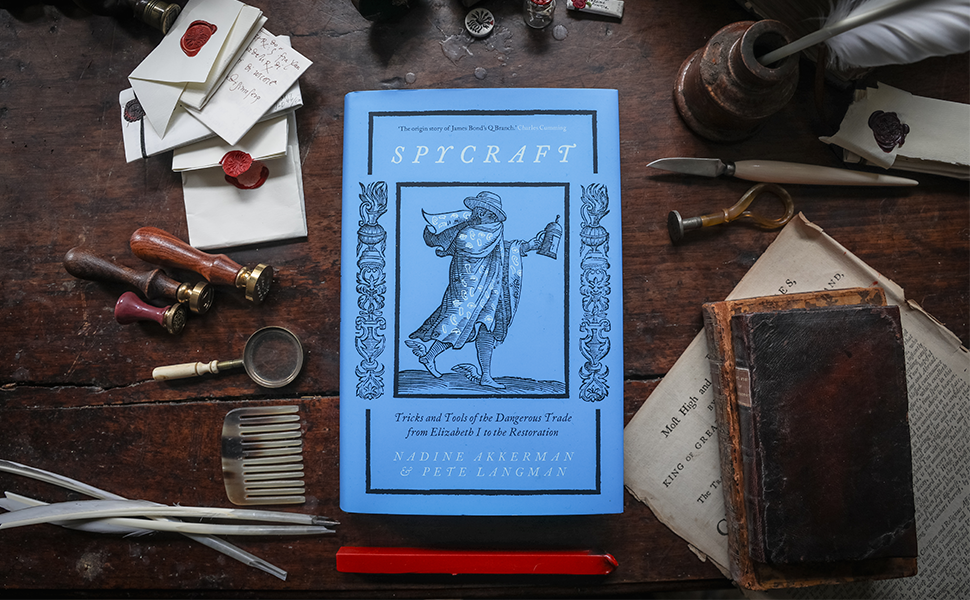

An extract from Spycraft: Tricks and Tools of the Dangerous Trade from Elizabeth I to the Restoration, out this week in paperback.

We think of disguises, whether of words, letters or people, in terms of avoiding suspicion, of replacing true identity with something innocuous such that the item or person in question might remain hidden in plain sight. There is, of course, another aspect to disguise—that of making something appear grander or larger than it is in reality. Such physical sleights of hand might include misinformation, such as Elizabeth Stuart, sometime queen of Bohemia, sending a letter describing the duke of Buckingham’s calamitous attempt to sack the port of Cádiz and plunder Spanish treasure ships in 1625 as a qualified success to a friend in the sure knowledge that it would be intercepted by the enemy. This type of disguise could also be reproduced on a personal scale. Perhaps the most audacious example of this was carried out by Thomas Douglas, a Scotsman who, apparently aggrieved at his lack of preferment, unleashed a series of events that saw him counterfeiting rather more than a few letters.

At around the same time that Christopher Porter was arrested for counterfeiting the signature of Robert Cecil, the Secretary of State numbered the glibbery Thomas Douglas amongst his intelligencers. Douglas was nephew to a notorious forger, the parson of Glasgow Archibald Douglas, a man thought by some to be involved in the murders of David Rizzio and Henry, Lord Darnley, respectively the secretary and husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. Many believed him responsible for the Casket Letters of 1567. He was certainly behind a series of forgeries that ‘implicated Esmé Stewart, Duke of Lennox, in popish plots’. He had also served as a spy for Francis Walsingham in 1583, and soon after was appointed Scottish ambassador in London. While Archibald had died in poverty in 1602, his nephew Thomas might be forgiven for believing that, with a late but infamous ambassador for an uncle and an influential employer in the shape of Cecil, the accession of King James VI of Scotland to the throne of England in 1603 would be the making of him. The Secretary of State appears not to have held his Scots intelligencer in particularly high esteem, however, considering some of his ‘intelligence’ to be arrant nonsense, while allegedly dismissing him as ‘an open-mouthed fellow, and apt to lie’. He thus employed him solely at the grittier end of business. When the expected smooth and graceful slide into a position at court through which he might enrich himself failed to materialise, Douglas took matters into his own hands. He fell in with two other disaffected Scots, James Stewart and Robert Wood, and the trio promptly pooled their resources in order to seize what they considered their just deserts.

Douglas was already, like his uncle before him, an accomplished counterfeiter. In January 1604 the three men set about forging documents granting the bearer the right to provide a particular set of goods or services, which they promptly sold to a merchant for the tidy sum of £300 (around £40,000 today). Such highly lucrative licences were granted by the crown, and often represented a thank-you for services rendered. These letters were authenticated by the monarch’s sign manual and the signet. Unfortunately for the intrepid trio, the Treason Act of 1554 had made the counterfeiting of the sign manual and the signet as dangerous as counterfeiting the Great and Privy seals. Douglas, Stewart and Wood were now guilty of treason. On hearing the news that the merchant who had bought their forgeries had not only been arrested for possessing counterfeit papers but had immediately declared that he had received them ‘from a Scot’, Douglas and Wood decided that they ought take a protracted sojourn to Calais in the interests of their continued good health. Stewart either elected to remain in London or was arrested before he was able to flee. In any case, he was subsequently tried and executed for treason, while Wood and Douglas were exiled in absentia.

While this foray into the dark side had netted Wood and Douglas considerably more money than Christopher Porter might have hoped to clear in even a year of dedicated and flawless forgery using his signature-stamps, the risk assumed had also been somewhat greater: while the act might well have endangered Porter’s ears, forging Robert Cecil’s signature was not treason. It was from his temporary base in Calais that Douglas promulgated a far more audacious act of forgery. Rather than counterfeiting a mere document, Douglas counterfeited himself, and in doing so would almost bamboozle an entire continent.

On 2 August 1604, a man ‘of medium height, wearing a light beard, sharp-featured, and with prominent eyebrows, and lacking several teeth’ presented the Grand Pensionary of the Dutch Republic, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, with a letter from the new king of England, James I, in favour of one ‘Robert Gray, a Gentleman of our Bedchamber’. The letter was as fake as the man who presented it. ‘Robert Gray’ was the invention of Thomas Douglas. Nevertheless, it appears that Oldenbarnevelt was impressed with this new ‘sharp-featured’ face at court, to the point of offering the Scot a commission in the Dutch army. Douglas, or Gray as he now presented himself, had not come all this way to be a soldier, and so returned to Calais where he promptly offered his services as intelligencer to the port’s governor, Dominique de Vic. Douglas had already planned his next trip, to the heart of the Spanish Netherlands, and he thought de Vic might forward him some money in return for information gathered there. Douglas appears to have been a persuasive individual, as while de Vic refused his kind offer of possible secrets in the future in return for ready cash in the present, the Scot still managed to convince the governor’s son that a loan of £10 was perfectly safe. And so, coffers bolstered, and armed with another letter of introduction, Douglas once again assumed the identity of ‘Robert Gray’, and made his way to Brussels. On his arrival, he suggested to Archduke Albert, who ruled the Spanish Netherlands alongside his wife Isabella Clara Eugenia, that he might help enlist Scots and English soldiers to support the Spanish in their campaign against the rebellious Dutch—not something that would have pleased his new friend Oldenbarnevelt. While Douglas did not in the end carry out this task, the trip was hardly a failure, as he returned to Calais clutching 100 gold pieces, a token of friendship given to him by Blasius, Archduke Albert’s secretary.

Having tested his handiwork in The Hague and Brussels, and thus convinced that his credentials were sufficient to persuade Protestant and Catholic powers alike, Douglas upped his game. Using a new set of letters that introduced him as a special envoy of King James, he embarked on an embassy to the courts of the German Electors, the four princes and three bishops who were responsible for choosing the Holy Roman Emperor—the emperor-in-waiting was traditionally installed as such by having the title ‘king of the Romans’ conferred upon him. Even though Douglas appears to have suggested that his mission was very hush-hush (presumably in order to explain why an ambassador would turn up at a European court with no retinue), flying below the radar did not mean he did not need to look the part, and alongside his letters of introduction and his undeniable chutzpah, he sported a grand-looking ambassadorial chain stolen from the son of the Polish ambassador in London.

The first port of call on the whistle-stop tour of ‘Robert Gray, ambassador to the newly installed king of England’ was the seat of the archbishop of Cologne. The simple act of undertaking the 250-mile journey perhaps in itself suggests the measure of Douglas’s seriousness, and on arrival he not only found his expenses defrayed and his arms laden with gifts, but it appears that he so beguiled the senators that they wrote to James by way of response to the message he brought. As it happened – and whether by chance or design is something of a mystery—there was another prestigious visitor in town, the papal nuncio. Hearing of Gray’s presence, the nuncio invited him to a formal banquet, where the two of them discussed the possibility of King James being elected to the imperial dignity.

“Wherever the idea had come from, it appears that Douglas had, in a heartbeat, moved from counterfeiting an ambassador to counterfeiting England’s geopolitical strategy.”

At first glance this seems a ludicrous idea, but rumblings of discontent were stirring. The current emperor, Rudolf II, had instigated a war with the Ottomans which was hurting many of the Electors where they felt it most deeply, in their purses. The fact that his younger brother Matthias, who was most likely to replace him, was particularly anti-Protestant did not help matters either. Matthias had not, however, been officially elected king of the Romans, so technically there remained a way of saving the situation. However unlikely it might have seemed, James was already considered to favour peace over war as a general principle, and, while a committed Calvinist, was known for his toleration of Catholics in general. What was more, he had already been in contact with the Pope in the run-up to the death of Elizabeth I (though he denied it, naturally, and his secretary Sir James Elphinstone had been made a scapegoat for the rumours). Indeed, both Spain and France had allegedly promised to support his claim to the English crown should he promise tolerance of Catholics once he ascended the throne. Had negotiations reached up to this level, then they would certainly have involved Cecil, who was working for both Elizabeth and James in the months before the succession question was rendered absolutely imperative by the English queen’s death. Douglas would later assert that Cecil knew all about his mission. Spreading such a rumour was certainly within Cecil’s ambit, but it seems more likely that there was an amount of wishful thinking going on. As Francis Bacon sagely observed, ‘man would rather believe what he wishes to be true’. Wherever the idea had come from, it appears that Douglas had, in a heartbeat, moved from counterfeiting an ambassador to counterfeiting England’s geopolitical strategy.

Douglas’s visit to Cologne was successful on many levels, not least financially—he set out on the next leg of his embassy in a coach lent to him by the papal nuncio and accompanied by a new luxury alongside the many gifts he was now laden with: three newly hired servants. At a mere 18 miles, the journey to see the archbishop of Trier in Bonn was somewhat shorter than his trip to Cologne had been, which must have come as some relief: it also proved rather less successful. The archbishop of Trier treated ‘Gray’ with enough suspicion to make him move on almost immediately to Aschaffenburg (a journey of almost 125 miles), where he spoke with the next spiritual Elector on his list, the archbishop of Mainz, who ‘entertained me sumptuously, gave me presents and provided me with a coach and lackeys’. Whether or not Douglas was serious in his ministrations, truly believing that he was well on the way to securing the four electoral votes that would guarantee James’s election as king of the Romans, or whether his treatment in Cologne and Mainz had made him overly ambitious, the wheels were about to come off his (borrowed) coach.

The fourth—and final—leg of Douglas’s journey saw him travel to Heidelberg, the seat of the Elector Palatine. Explanations differ as to exactly what it was that made the Calvinist Friedrich IV suspicious of this Catholic ambassador purporting to come from England’s new king, but familiarity doubtless played a part—unlike the Catholic Electors, who had seen no good reason to engage with the Calvinist king of a relatively minor European country, Friedrich had dealt with James when he was only king of Scotland. Whatever the reason, Friedrich saw enough in the ambassador’s documents to believe that they were not what they seemed, and promptly threw the Scotsman into jail, sending a message to James asking whether he should send the miscreant back or deal with him in situ. Much to the prisoner’s chagrin (Douglas begged Friedrich to instead send him to fight the Ottomans, a move perhaps only marginally less likely to result in a grisly demise), James wanted him back, possibly in order that he could better scotch the rumour that he desired the imperial crown. (This was not the last time that James’s friends in Europe would help him; Friedrich would later repeat the favour when William Baldwin, a man thought complicit in the Gunpowder Plot, turned up in the Palatinate but was also sent home to meet his fate.)

Douglas eventually made three confessions, two in the dungeons of Heidelberg and one in London’s Tower. These confessions are as slippery as the man himself, and tell different stories. Douglas first takes responsibility for writing the letters himself, before changing his story and insisting that ‘they were written to his dictation by a poor Frenchman lodging “in an alehouse near the tennis court in the Blackfriars” ’. He first blamed the conveniently disembowelled Stewart (whose spiral-locked plea for clemency had proved unsuccessful) for the initial counterfeiting of the king’s signature, suggesting that he obtained the Privy Seal of Scotland with which he had provided the final authorisation by borrowing it from his brother James, who worked for the Scottish secretary Elphinstone. Eventually, he confessed that ‘in truth he caused the said Privy Seal to be counterfeited, and therewith sealed six letters, unto six Princes of Germany [i.e., all the Electors bar the king of Bohemia], counterfeiting the king’s hand to every one of them’. Wherever the truth lies, it seems that the successful counterfeiting of documents was a joint enterprise – clumsily counterfeited documents could slip through unnoticed if the official checking them either lacked familiarity with their usual form or simply could not be bothered (or did not desire) to inspect them fully.

The story of Thomas Douglas shows that the counterfeiting of documents was no mere matter of petty fraud or even exposing conspiracies. In the wrong hands, it could potentially change the course of history. Douglas left England in June 1604, and spent much of the next seven months living it up as ‘Robert Gray’, his one-man embassy blazing a trail through some of the richest courts in Europe, negotiating (if he is to be believed) for King James to accede to the imperial throne. At the end of January 1605, Gray had arrived in Heidelberg, where his embassy juddered to a halt. By the end of May, he was being escorted back to England, Thomas Douglas once more. On 24 June, he was committed to the Tower, his fate all but sealed. After a brief trial, Douglas was found guilty of treason and other ‘prancks’, and put to death. His brief time in the spotlight shows us something of the sheer power and authority the royal sign manual carried with it, especially when wielded by a man who must have possessed no little charisma. It is no hyperbole to say that Robert Gray, ambassador to King James, was a disguise Thomas Douglas created with nothing more than a signature, a seal and outrageous self-confidence.

Spycraft: Tricks and Tools of the Dangerous Trade from Elizabeth I to the Restoration by Nadine Akkerman and Pete Langman is out in paperback this week (although the hardback cover glows in the dark!)