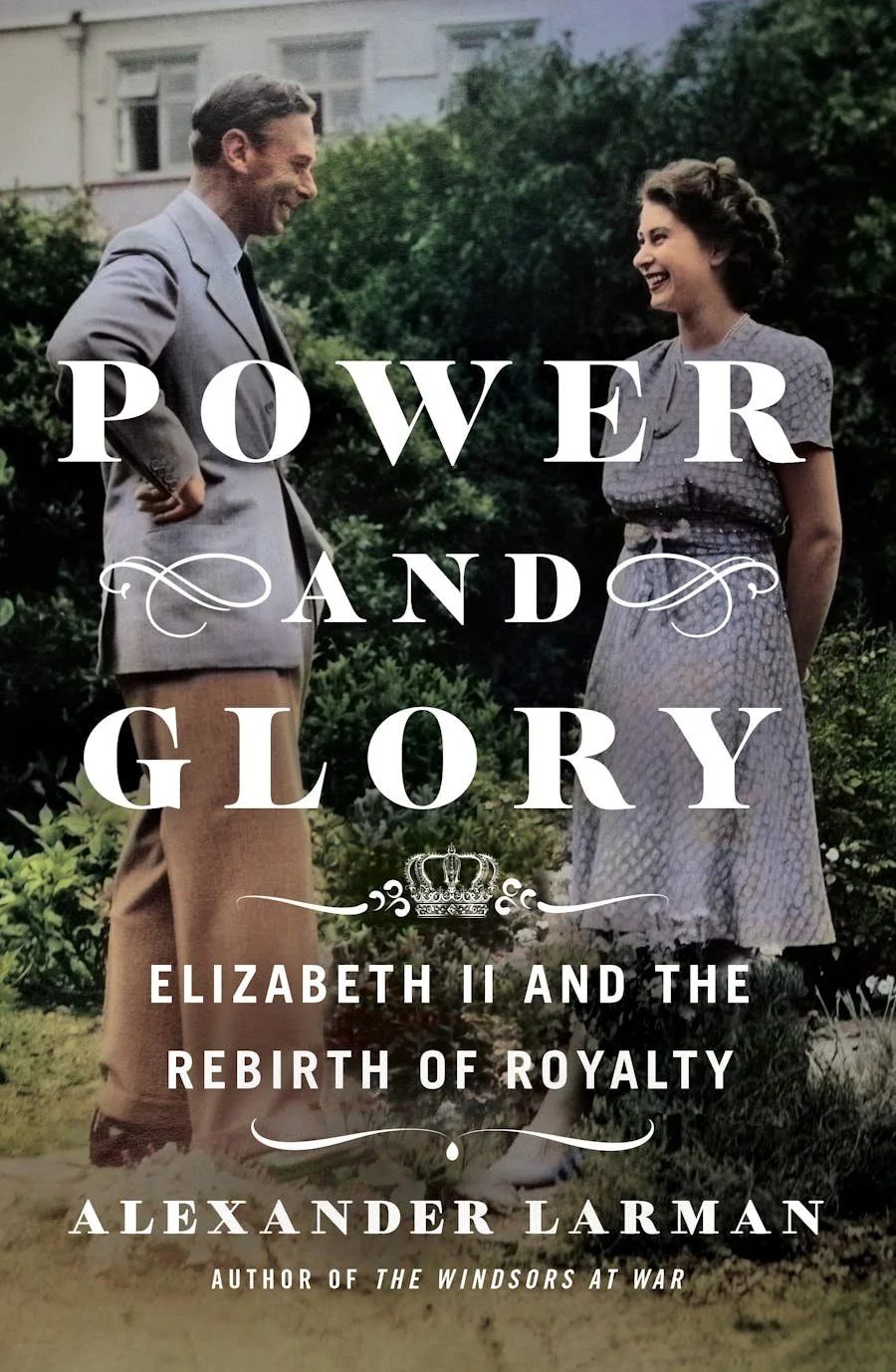

Power and Glory

by Alexander Larman

March 2024

How It Started… How It's Going. Alexander Larman writes his way into a trilogy about the Windsor family.

When I sat down to write The Crown in Crisis in late 2018, it was without any intention of the book becoming the first part of a trilogy. Indeed, in all its drama and richness, the saga of Edward VIII’s abdication seemed like a perfectly self-contained story. But long before I finished I found I was desperate to continue that narrative, which concluded with the exiled former king heading into Europe under cover of night.

Writing its sequel, The Windsors at War, it was a particular thrill to be able to draw upon a vast amount of rare and unseen material, giving insight into everything from the fractious relationship between King George VI and his disobedient brother (the now-Duke of Windsor) to the extent to which the Nazi sympathies of leading courtiers permeated Buckingham Palace even at the commencement of the Second World War.

Yet when I finished Windsors I was caught in a dilemma.

It seemed clear that the logical next step was to wrap up the whole era I had embarked upon—and that therefore I needed to write a third and final book, that would begin with VE Day and follow the story up until the coronation of Elizabeth II.

My fear, though, was that it would be anti-climactic compared to the other two. Those books had been steeped in grand, operatic themes of betrayal, power and a family torn apart by war and treachery. If this one could offer nothing more dramatic than a royal wedding, the slow death of a king, and a coronation, was it really worth the effort?

It will be for my readers to judge for themselves as to whether I have succeeded; but Power and Glory has proved every bit as thrilling and revelatory to research and write as the earlier books, exploding any belief that I had that this period was somehow less eventful.

The focus this time lies with three separate protagonists: the young Princess Elizabeth, whose marriage and family life is increasingly coloured by knowledge of the awesome weight of responsibility she will be taking on; George VI, whose already fragile health was dealt a terminal blow by the strain that the war placed him (and his country) under; and, naturally, the Duke of Windsor, seeking to pursue his own agenda and to hell with the consequences.

As in my other books, I have attempted to be fair towards the Duke—but the man does not make it easy for even the most generous of biographers to portray him in a warm and sympathetic light!

Last year, I stayed at a hotel in Paris that he and Wallis Simpson used to frequent, and, unable to sleep, wondered what the chances were of a spectral visit from an outraged Edward, chastising me for his presentation in these books. Had I been taken to task by his apparition, I hope that I should have had the presence of mind—shortly before telephoning the concierge and asking for bell, book and candle!—to reply that nothing I have said about him in the trilogy is based on anything other than meticulously-documented fact: usually, and most damningly, his own entitled words. Unlike fine wine, the once-Edward VIII has not improved with age.

“Unlike some of my historian peers, I have always attempted to look at the Royal Family with clinical detachment.”

But if the Duke supplies much of Power and Glory’s high drama (and, at times, comic relief), then it is his brother’s story that constitutes its tragic arc. George VI was the monarch who never wanted the responsibility of the role, and it is testament to his belief in duty that he committed himself to its onerous burdens, even as it became increasingly clear that the strain was having a terrible effect upon his health. I have attempted to present George as a rounded character, neither sanctifying nor belittling him, and I hope that my depiction of a man whose greatest strengths were perhaps domestic, rather than regal, is one that frames this book as fundamentally a human story.

If the book has a heroine, however, it can only be the future Elizabeth II.

After making only fleeting appearances in The Crown in Crisis and The Windsors at War, I am finally able to give Her late Majesty the full measure that she deserves, bringing her to life in both private and public spheres.

If my first book was a ticking-clock suspense thriller set against the backdrop of something thought constitutionally unprecedented, and the second a wartime saga that explored a dysfunctional, squabbling family tested to its limits, so this one, too, has a simple story at its heart: an account of a close and loving father-and-daughter relationship, albeit one where the father is dying and the daughter is facing upheaval and change on an unimaginable scale.

Both of my earlier books were intended, to a large extent, as black comedies of manners. But Power and Glory is different. While, say, writing about the Duke of Windsor’s misdemeanours never ceased to amuse, this time around I was struck by how often I would attempt to finish a chapter and be unable to type because I was weeping so copiously. Even now, certain lines—“I felt that I had lost something very precious”; “my whole life whether it be long or short shall be devoted to your service”—still have an utterly Pavlovian effect upon me.

I was still only mid-way through writing this volume when I learned of the Queen’s death on 8 September 2022—and, like a vast number of other people in Britain, I felt as if one of the aspects of my life that had been forever constant was removed from me. Amidst the millions of words written about her in the subsequent days, by sources sympathetic, hostile or otherwise, there was one central point universally acknowledged: in both her remarkable longevity, and lifelong dedication to service, she was a monarch sans pareil. It is therefore appropriate that Power and Glory should chart the end of one era—of one Britain, even—and the birth of a new one. The book may be a tragedy, and a requiem for a lost nation; but it is also a paean of praise to the woman who redefined the country in her image.

After all that, it may come as a surprise to readers to learn that I am not a monarchist. Unlike some of my historian peers, I have always attempted to look at the Royal Family with clinical detachment, rather than from the perspective of a fully paid-up admirer of what strikes me as a deeply-flawed and anachronistic institution. Certainly, the ludicrous indulgence offered to the Duke of Windsor—a man who should have gone to prison during WWII for treason, and ideally remained there—shows the worst aspects of ‘the Firm’ and the noblesse oblige offered to its members, regardless of their activities.

That said, the virtues that the Windsors at their best exemplified were real, too: courage, generosity, compassion and a dedication to serving their country, rather than themselves. When I finished writing this book, I had to restrain a genuine urge to leap onto my desk and shout “God Save the Queen!” If I am a republican, I’m a decidedly-imperfect one indeed. But should this final volume in the trilogy engender a similar urge in just one reader, I will proudly consider my duties as historian and biographer fulfilled.

Power and Glory: Elizabeth II and the Rebirth of Royalty is out on 28th March.